Gut-brain axis I: Gut bacteria and brain health

It IS true - the human brain and gut are intimately connected through a complex system called the gut-brain axis.

This connection allows the gut microbiome — the huge community of bacteria and other microorganisms in our guts — to influence brain function.

Ways our microbiome and brain talk

The gut and brain communicate through the nervous system, immune system, and various biochemical pathways.

The vagus nerve, which runs from the gut to the brain, is a major route of this communication in the nervous system.

Gut bacteria produce substances that the vagus nerve detects and sends as signals to the brain, influencing mood, stress levels, and inflammation. In turn, the brain uses the vagus nerve to control digestion, gut health, and even immune responses locally in the gut.

That's one of the reasons scientists are studying ways to improve gut-brain communication by vagus nerve stimulation.

Certain bacteria in the gut can ferment molecules into neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. The guts release these potent neurotransmitters, chemicals that play an important role in our mood level and in cognition.

The gut also produces short-chain fatty acids, which can reduce inflammation and help maintain the integrity of the blood-brain barrier.

When the balance of gut bacteria is disrupted, a condition known as dysbiosis, it can lead to increased gut permeability. This allows harmful substances to enter the bloodstream and trigger inflammation, which may contribute to brain disorders.

How does the microbiome become bad?

Factors such as diet, pollution, and antibiotic use can impact the gut microbiome and, in turn, brain health.

Diet plays a crucial role in shaping the gut microbiome. Diets rich in fiber from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains promote the growth of beneficial bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids, which support gut health and reduce inflammation. In contrast, high-fat and high-sugar diets can decrease bacteria diversity and favor bacteria linked to metabolic and inflammatory diseases.

Fermented foods such as yogurt and kimchi introduce probiotics that can enhance microbial balance. Artificial sweeteners and emulsifiers, common in processed foods, have been shown to alter gut bacteria and may contribute to metabolic disorders.

Luckily, the microbiome can rapidly respond to dietary changes, with shifts observed within days of altering food intake.

Antibiotics, while essential for treating infections (and our survival as a species), can disrupt beneficial bacteria, potentially affecting cognitive function. Some research suggests that eliminating harmful gut bacteria through targeted antibiotic use might improve cognitive performance, but this remains controversial.

Air pollution is another environmental factor that may affect the microbiome and may contribute to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Fine particles from pollution can enter the brain and trigger inflammation, potentially accelerating disease progression.

The role of gut microbiome in diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, have been linked to changes in the gut microbiome.

Research has shown that people with these conditions often have an altered gut bacterial composition compared to healthy individuals.

Some bacteria (such as Escherichia and Shigella) have been found in greater numbers in Alzheimer’s patients and are associated with inflammation.

On the other hand, beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium help maintain an anti-inflammatory environment, which may protect against neurodegeneration.

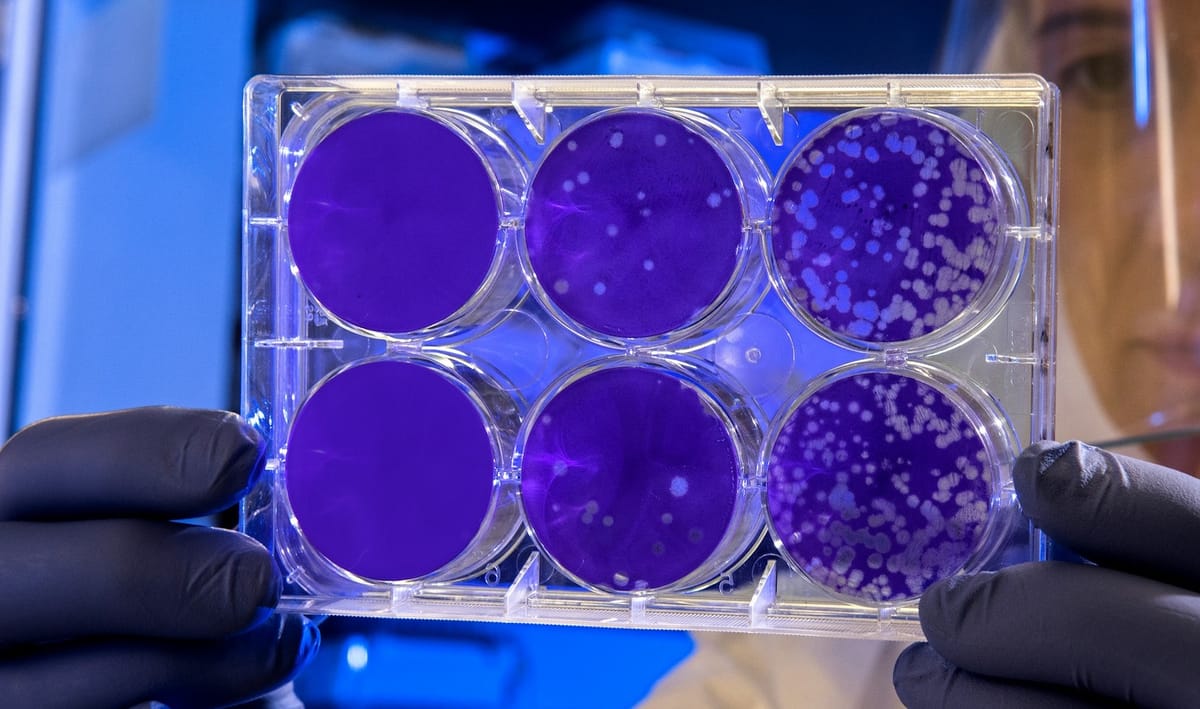

The connection between gut bacteria and brain health is supported by research on fecal microbiota transplantation, a procedure that transfers gut bacteria from a healthy donor to a patient. This technique has been shown to improve symptoms in neurological disorders, including Parkinson’s, by restoring a balanced microbiome.

Dementia and the microbiome

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, with progressive memory loss and cognitive decline. In the microscope, the disease is marked by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles in the brain cells, which lead to brain cell damage and death.

Recent studies suggest that gut bacteria might play a role in the development of these harmful protein deposits. Researchers have found that specific bacterial strains can increase the production of amyloid proteins in the brain, while others may help clear these proteins before they become toxic.

Studies in mice have demonstrated that modifying the gut microbiome can influence disease progression. For instance, in mouse models of Alzheimer’s, the absence of gut bacteria reduced the accumulation of amyloid plaques in the brain cells.

Additionally, certain bacteria produce metabolites that influence neuroinflammation, both increasing and reducing it. Increased inflammation in the brain is a key factor in Alzheimer’s progression.

Potential treatments of dysbiosis

Emerging studies suggest that gut microbiome manipulation could be a promising therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases. By altering the gut microbiome, it may be possible to slow down or even prevent the development of the disease.

Scientists have investigated the effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics on Alzheimer’s mouse models, finding that prolonged use of these drugs altered gut bacteria composition and reduced inflammation.

Other research has focused on identifying specific microbial metabolites that impact cognitive function. For example, high levels of certain bacterial byproducts have been associated with cognitive decline, while others may have protective effects.

Nutritional interventions and probiotic supplements are being explored as potential ways to restore a healthy gut microbiome and support brain health.

And then there are the fecal transplants. Sounds dodgy, right? But it may be the new black in the treatment of neurological diseases. The next blog post theme is fecal transplants and brain health.

About the scientific papers:

First author: Maria De Angelis, Ilario Ferrocino, Italy

Published: Nature Scientific Reports, 2020

Link to paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-61192-y

First author: Amanda A. Menezes, USA

Published: Brain Sciences, December 2024

Link to paper: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/14/12/1224

Comments ()